Drug Mixer and Auto-Injector

Due to the confidential nature of this project, certain details have been omitted.

Overview

While working for Helbling Precision Engineering, I was part of a two-person team tasked with developing an automated drug mixing and delivery device. Each of us focued on the development of one concept, ultimately delivering two innovative proof-of-concept (POC) devices to our client, who was very satisfied.

Unique Challenge

There were two key requirements of this project that created a unique design obstacle.

- The device must cyclically mix a high-viscosity drug once activated, up to 30 cycles/minute, preferable with a single user inputs.

- The device must be fully mechanical - no electronics.

The Solution

We utilized a ground-up engineering approach - starting with defining individual device functions, generating ideas for mechanisms that accomplish each, combining these ideas into practical concepts, then preliminarily evaluating these concepts based on the requirements provided by the client (Figure 1). We identified a handful of promising solutions, and ultimately selected two to progress to a POC prototype phase.

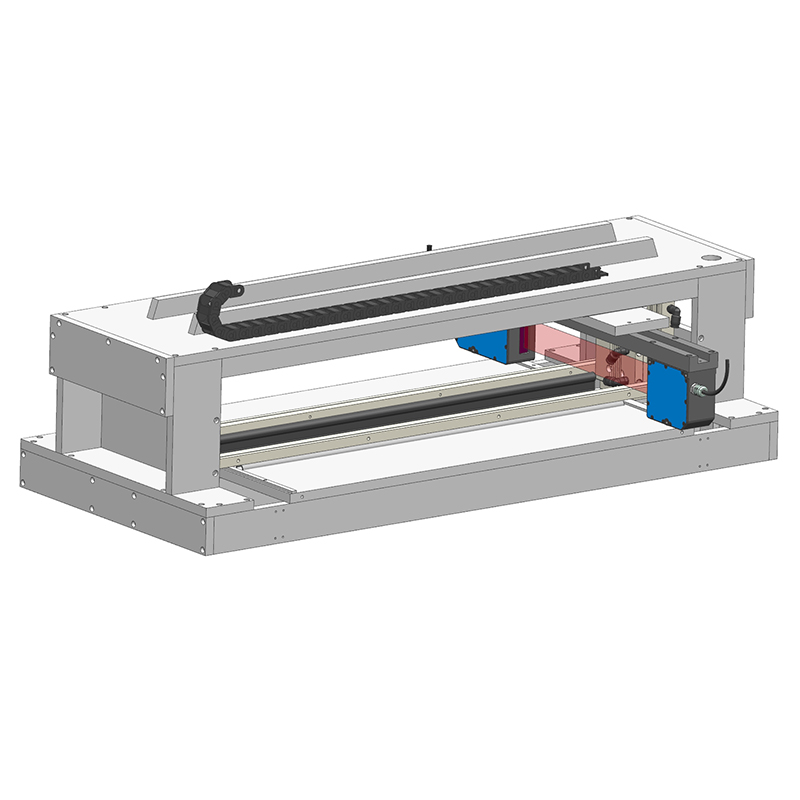

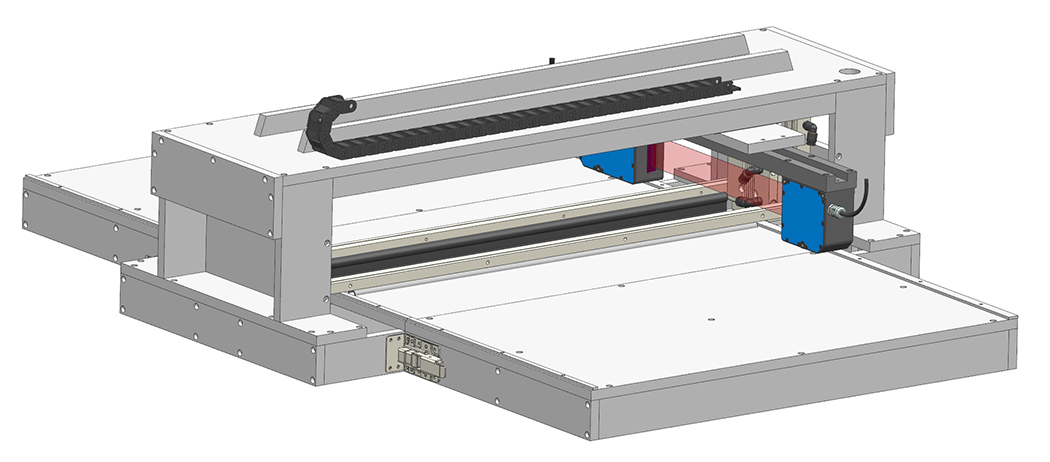

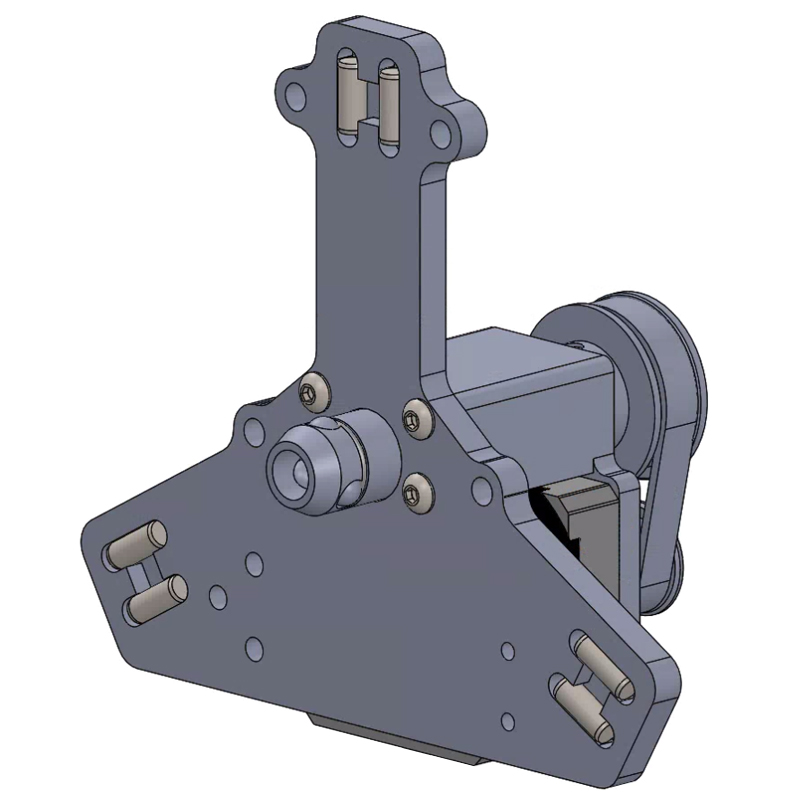

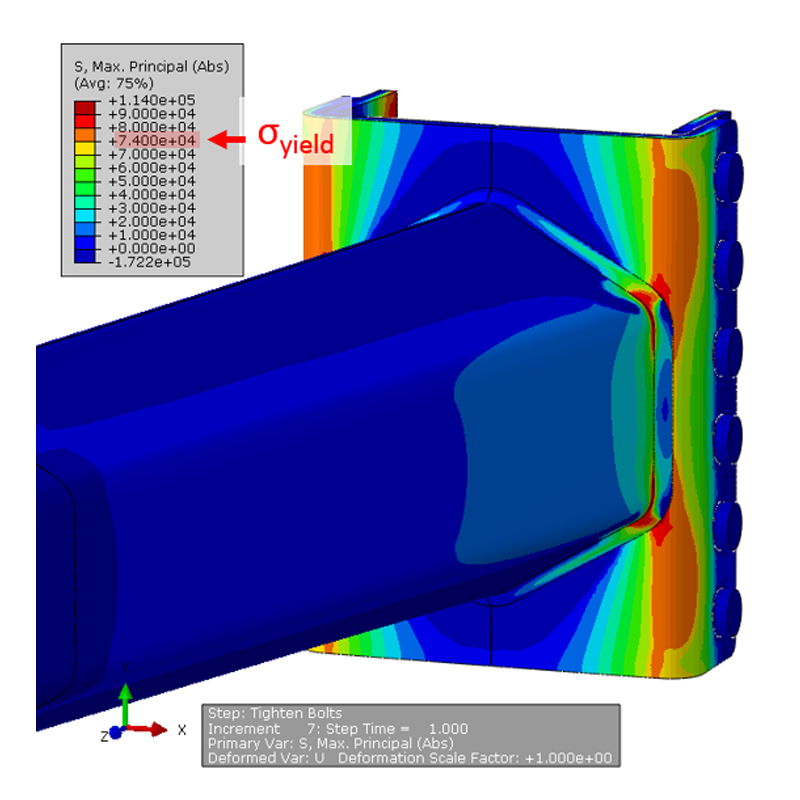

The concept I was primarily responsible for developing utilized a compressed gas cartridge and internal valving to mix the drug. Once activated by the user, a complex system of mechanisms enabled a small number of user inputs to achieve the significant number of required device states. With each intermittent button press, the internal mechanism states changed to generate a mixing cycle. The final POC demonstration is shown in Video 1.

Video 1: Demonstration of proof of concept prototype functionality. Device achieved all performance requirements set by client.

Though a prototype, DFMA principles were considered throughout the design, and several COTS parts were utilized as possible. All in all, the development of this concept over a short 5 month period was received exceptionally well by the client, and they ultimately ended up pursiing this concept as their primary development path.

What I Learned

This was the first project that I was responsible for the complete development of a device from idea generation through prototyping. It challenged my understanding of pneumatics and DFMA, and required revisiting many engineering subjects not leveraged since my education. Additionally, with user experience being core to the success of the concepts, I spent a significant portion of the development thinking about not just how to accomplish the mechanical tasks, but also ensuring the use case remained simple and intuitive.